It sounds straight-forward. Physicians and other healthcare stakeholders want to exchange health information electronically with various stakeholders around the country. Can it be done? Perhaps, but with a lot of behind-the-scenes transfer of the information using one or more direct interfaces, health information networks (HINs), and/or health information exchanges (HIEs), some of which have attempted a more national scope but still fall short of what’s needed. And there’s the potential for many roadblocks along the way because those entities operate with varying business models, technical requirements, consent models, and geographic market areas, not to mention the fact that not all connect with each other.

In short, currently there is no seamless way to share medical records and patient data on a national scale. That’s the problem ostensibly that TEFCA -- the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement -- is trying to address. As called for by the 21st Century Cures Act of 2016, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) and their chosen (and funded) Recognized Coordinating Entity (RCE), The Sequoia Project, are fleshing out the details and scope of TEFCA albeit in fits and starts. The first set of final agreements and accompanying technical, operational and business requirements are expected to be rolled out in the first quarter of 2022 (and maybe as early as January).

Here’s my perspective on where TEFCA has been and where it is likely to go.

How TEFCA Is Expected to Work

TEFCA is a set of contracts, policies, and standards to support the development, governance, and operation of a national system that offers secure, electronic health data exchange. The goal is to create a single “on-ramp” for any healthcare entity (including individuals) to the numerous health information networks and exchanges that exist (and may come online in the future) and exchange information with any other entity that is also connected within the boundaries of certain exchange purposes. TEFCA emphasizes access, scalability, transparency, privacy and security, including identity proofing and authentication. The Common Agreement is the contract for the basic legal and technical requirements supporting standardized, trusted exchange among participants.

TEFCA is a set of contracts, policies, and standards to support the development, governance, and operation of a national system that offers secure, electronic health data exchange. The goal is to create a single “on-ramp” for any healthcare entity (including individuals) to the numerous health information networks and exchanges that exist (and may come online in the future) and exchange information with any other entity that is also connected within the boundaries of certain exchange purposes. TEFCA emphasizes access, scalability, transparency, privacy and security, including identity proofing and authentication. The Common Agreement is the contract for the basic legal and technical requirements supporting standardized, trusted exchange among participants.

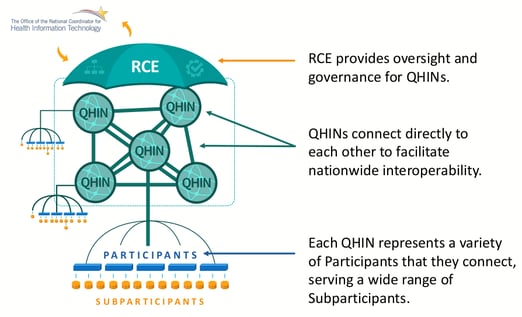

TEFCA establishes a backbone of connected super nodes, called “Qualified Health Information Networks” (QHINs), which other HINs, HIEs, healthcare organizations or even individuals will connect to (either directly as participants, or connected to participants as sub-participants). QHINs will operate in a standardized way to enable interoperability, security and connectivity. Details are spelled out in the QHIN Technical Framework (QTF), which describes the functional, technical, and operational requirements that organizations must meet to become a QHIN. QHINs will begin to launch later in 2022 and will roll out (perhaps in waves) as QHIN applicants complete the approval process.

So far, a handful of organizations (most already operating exchanges at scale) are expected to become QHINs (out of the hundreds that exist) or to at least have a major seat at the TEFCA governance table. They include:

- The eHealth Exchange – the nation’s largest network, and the most straightforward way to connect with federal agencies, such as the Social Security Administration

- CareQuality – a “network” of organizations that subscribe to a standardized exchange framework

- CommonWell – a services network of mostly EHR vendors – has a relationship with CareQuality

- DirectTrust – Supporting the Direct secure email protocol and dozens of Health Information Service Providers (HISPs)

- The Strategic Health Information Exchange Collaborative (SHIEC)– the trade association of state-based HIEs. SHIEC has launched its Patient Centered Data Home which is a method for data exchange between HIEs. SHIEC also recently joined forces with the Network for Regional Healthcare Improvement (NHRI) to form Civitas, a multi-stakeholder initiative that will target healthcare access, affordability, quality and equity by engaging with health information exchanges and health improvement collaboratives.

Other organizations, such as large state HIEs (some of which are banding together), organizations with experience running and advancing HIEs (e.g., Velatura/USQHIN), health IT interoperability vendors (e.g., Health Gorilla), and large EHR vendors (e.g., Epic), have either announced, hinted, or seem likely to attempt to become QHINS. The language regarding eligibility to apply is formulated to provide a clear path forward to existing national exchange efforts, and will provide some challenges for newer entrants, so it will be interesting to see how broadly it is interpreted and how many QHINs will be approved.

TEFCA’s status

As mentioned previously, the first of TEFCA’s final documents are due to be published as early as January 2022 (just a few short weeks away). Draft versions of different components of TEFCA have been issued since 2019, with many opportunities for public response. Sequoia has also held closed door discussions with a few dozen organizations that participated in the Common Agreement Workgroup (CAWG) with interest and means to become QHINs. One of the latest releases to the public came in September 2021, with a document entitled Elements of the Common Agreement. It was somewhat of a disappointment because it really was a table of contents for the upcoming TEFCA specifications instead of the actual proposed contract language and details. It really didn’t provide much insight unless one wanted to read between the lines. It did, however, provide the opportunity for ONC to ask for public comment. Not surprisingly, it garnered responses from many (four dozen) significant stakeholders, many asking for clarifications and expressing concerns for their particular interests. A supplementary document, the Draft Qualified Health Information Network Eligibility Criteria, was issued in early October, also with a brief public comment period. The comment period for both documents has closed. Comments are posted on the Sequoia website; they offer a glimpse of what stakeholders (particularly the “Big Dogs”) think the final versions should contain. The RCE continues to hold forums for stakeholders to provide feedback.

Challenges and Opportunities

To be sure, TEFCA is a work in progress and many issues are outstanding. Some may be addressed in the forthcoming final TEFCA guidance. Others may be resolved in the longer term, likely in phases. Here are some big concerns that complicate TEFCA’s rollouts.

-

Harmonization with state laws. TEFCA is a national initiative, which currently must coexist in a country governed by state laws concerning the privacy, security and sharing of clinical and administrative health information. Harmonizing those myriad laws and regulations with TEFCA could take years, making life complicated for entities and patients desiring the proper sharing of their data. Legislation and subsequent rule making could make TEFCA adoption and participation mandatory, which would make its provisions a floor and create a standardized, national baseline (see more on this later).

- Harmonization with HIPAA. TEFCA must also coexist in the healthcare landscape with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). HIPAA’s provisions have been slowly implemented since enactment in 1996. It specifies the use of certain transaction standards, primarily from ASC X12, and limits its authority to certain health entities for treatment, payment and operations. As a result, many existing HINs do not support data exchange for other use cases, such as patient data sharing, public health reporting and population health management. There are also questions about to what degree TEFCA will support payment and operations exchange purposes, thereby affecting the business models for the clearinghouses. (Initially, it seemed like a lot, then a little, and now, a lot again.) Future updates of TEFCA will have to address its interactions with HIPAA requirements. As an aside, TEFCA’s entry on the healthcare scene may force the much-needed update of HIPAA.

- Interaction with information blocking provisions. Although TEFCA was formulated as called for by the 21st Century Cures Act, the legislation was most known for established prohibitions against information blocking by healthcare entities and vendors as well as promoting the use of open application programming interfaces (APIs) using HL7’s FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperable Resources) standard. Regulations fleshing out those provisions were issued in March 2020. (Click here to read our take on them.) Now stakeholders are wondering if an organization’s participation in TEFCA may be considered as evidence that it is not information blocking. And they are wondering about the converse—is an organization considered as blocking information exchange if it is not participating in TEFCA? Will the latter trigger enforcement? Guidance is needed to clarify this issue.

- Technology gaps. In an effort to ensure that existing (legacy) and proven interoperability infrastructure investment is leveraged and that TEFCA is able to operate at scale, TEFCA has taken a conservative approach. As such, it will be first released with some technology gaps, including lack of inclusion of some modern standards. Take HL7’s FHIR (Fast Interoperable Healthcare Resources) standard, for example. While FHIR is at the heart of 21st Century Cures APIs in support of point-to-point integration and is gaining traction for many use cases, ONC and the RCE do not feel it is proven enough at this time in such areas as passing on user credentials/consents thru the TEFCA QHIN network. However, the RCE is developing a TEFCA FHIR Roadmap, which is intended to layout the scope, timing, and transition requirements for QHIN-to-QHIN exchange via FHIR. The TEFCA FHIR Roadmap will be released with the final versions of the QTF and the Common Agreement, considering the industry comments received this fall.

On the other hand, there are some standards and technologies that will be needed for TEFCA but are not yet ready for prime time, and it is unclear to what degree they might be included within TEFCA vs relied on outside of TEFCA. These include patient matching, eConsents and creation of a patient directory. However, this is handled (e.g., centralized, federated, hybrid) will be essential for QHINs to accurately identify patients; take varying levels of consent into account (for example, a patient could share certain data with a mental health provider and deny access to that information to other providers); and accurately route the information.

There’s also the potential for capacity gaps. Scalability will be important. Can networks scale up fast enough to meet demand? Will the demand be there? What happens if one group of connected networks emerges as the most efficient? Users may flock to it and make it the preferred way to route health information across the country. Will there be enough capacity to handle such a flood of users? Would it drive other networks out of business?

-

Business models. As currently specified, QHINs will not be able to charge each other for data exchange, they will, however, be able to charge participants, who will, in turn, be able to charge sub-participants. (Note: TEFCA is attempting to ensure that the individual access service is not charged for.) So far, a fee schedule has not been released. How those charges are derived, structured, imposed and made more transparent could facilitate—and possibly even incentivize--stakeholder enrollment with QHINs. Or, they could have a chilling effect. An enforcement mechanism has yet to be developed. Presumably they will be published simultaneously in the near-term horizon.

Although TEFCA may have some traction with non-for-profit entities, it will have the most success if it can find a way to also support for-profit business models. How those shake out remains to be seen in terms of size, user fees, membership, market share and sustainability. There also are questions about how much consumer participation will materialize. One of the major concerns with 21st Century Cures was that if once consumers gave consent for a third party to request data on their behalf, it made too much information available to organizations outside of HIPAA protections. TEFCA, as currently formulated, requires HIPAA-type protections to all data it exchanges.

- Voluntary or mandated? TEFCA is voluntary at this juncture. While the government hopes that success will breed success, and incentives may be introduced to sweeten the offering, it won’t surprise many that at least some in the government hope that payers, providers and states advocate for it to become mandatory. There is precedent. Remember, Meaningful Use started out as a voluntary program.

In the meantime, the government has ways of making its “voluntary” requirements mandatory in certain circumstances, which in turn would flow down to the private sector. For example, connecting with a QHIN could be a condition of participation for Medicare, Part D plans and Medicaid. As Medicare goes, so goes the private sector.

- Patient participation. TEFCA clearly is intended to facilitate patients’ access to and exchange of their health data, whenever it’s needed and regardless of where the patient and provider are located. This is in keeping with recent initiatives to give patients access to their data and the tools to share it. Examples include Medicare’s BlueButton 2.0 and the 21st Century Cures Act’s interoperability rules, which are forcing quick creation and widespread adoption of APIs to enable data sharing among providers, patients and payers. Patients’ seamless access to — and sharing of — better-quality health data can empower them and put them firmly in the driver’s seat, allowing them to select providers and payers based on quality and cost and to understand the costs of different procedures, care settings, and coverage. That said, a lot of education will be needed to enable patients to access, understand and share their health data. Health care is a black box for most patients and health literacy overall is exceptionally low. In addition, many entities are not equipped to enable patient access and sharing of their data. Technical changes will be needed, as well as a cultural shift. Organizations that lag in including TEFCA in their strategic planning, do so at their own peril. On the other hand, those who embrace TEFCA quickly, should TEFCA succeed, will have competitive advantage.

Looking forward. TEFCA is an evolving program that is seeing renewed focus in today’s rapidly changing healthcare landscape. Point-of-Care Partners has helped many payers, providers and vendors understand how such initiatives as TEFCA affect their lines of business, technologies and market share. Let us put our expertise to work for you. Reach out to me at ken.kleinberg@pocp.com.