Fee-for-service was never designed for what chronic care requires. It rewards transactions rather than the long arc of behavior change, continuous monitoring, or coordinated team-based care. For years, the industry has talked about shifting to value, yet progress has repeatedly stalled, bogged down by disagreements over which outcomes to measure, how to collect reliable data, and how to coordinate across large care teams. And when it comes to prevention, the model falls even shorter. The strongest return often comes from early intervention, long before a crisis, but today’s payment system barely recognizes that work.

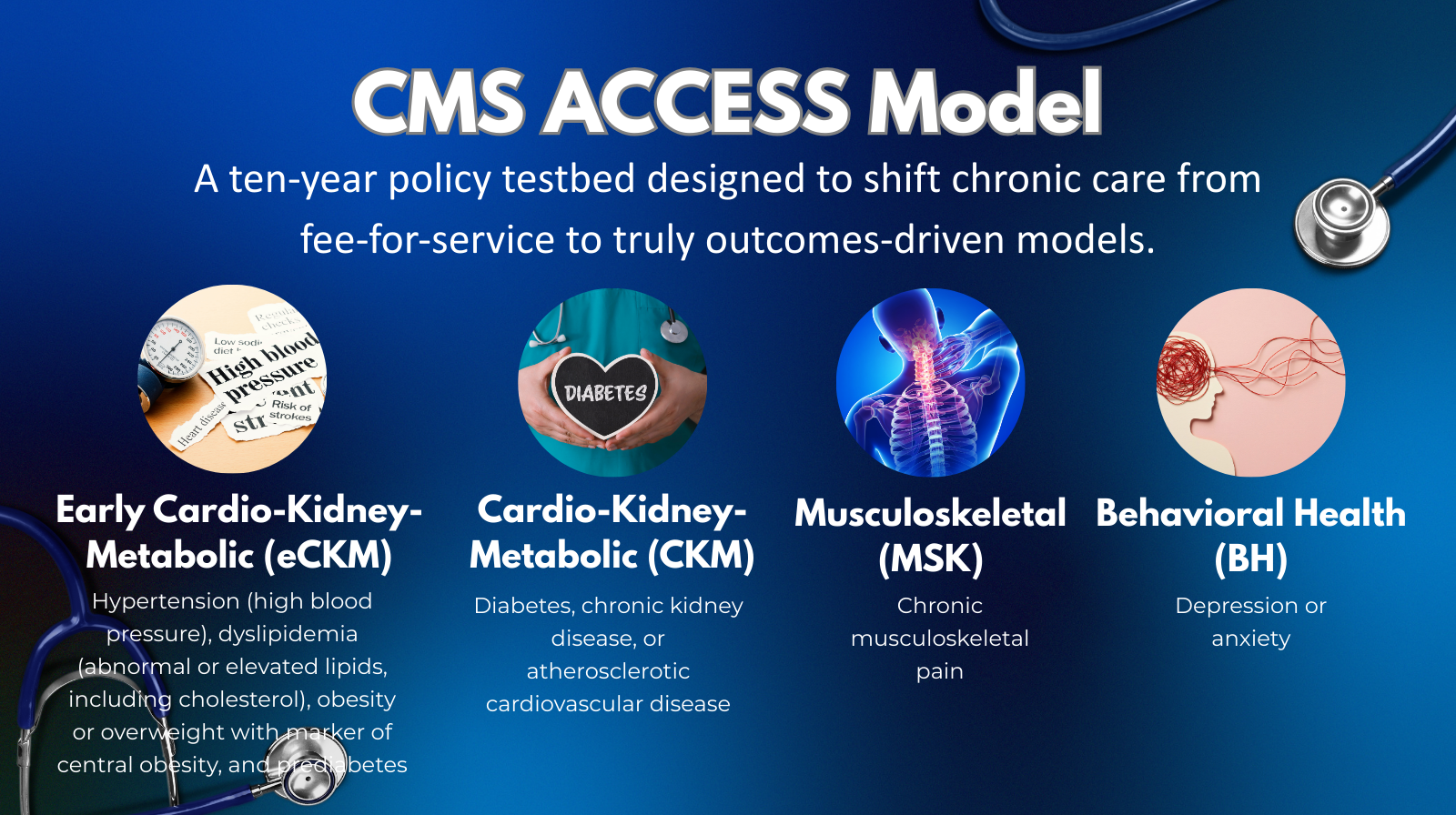

The new Center for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) Innovation (CMMI) payment model, Advancing Chronic Care with Effective, Scalable Solutions (ACCESS) Model, is designed to directly confront those limitations. It is not just another pilot. It is a long-term policy testbed that signals where federal payment reform is headed.

At its core, ACCESS is a voluntary CMS Innovation Center model that shifts reimbursement away from billing activities and toward paying for measurable improvements in chronic disease outcomes. Instead of compensating providers for visits or minutes spent on care management, ACCESS aligns payment to whether a patient’s condition improves. The model targets several of the most complex and costly areas of chronic care, including early cardio-kidney-metabolic risk, established diabetes and cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, musculoskeletal pain, and behavioral health conditions such as depression and anxiety.

Organizations receive recurring payments based on whether patients achieve defined clinical improvements, such as better blood pressure control, improved A1c levels, reduced pain, or improved behavioral health scores. This approach gives providers flexibility to use the care modalities that work best, including telehealth, remote monitoring, apps, and wearable technologies. For the first time in a CMS Innovation Center model, Medicare beneficiaries can also enroll directly, bypassing provider-only participation. That change alone signals a broader shift toward greater patient agency in care selection.

ACCESS creates a clearer business case for proactively managing chronic conditions at scale. Instead of forcing organizations to stitch together fragmented billing codes, it establishes a predictable revenue model tied to improvement. That stability makes it easier to justify investments in care teams, digital infrastructure, data integration, and patient engagement. It also lowers the barrier to entry for smaller organizations that want to participate in value-based care without joining a full-risk Accountable Care Organization (ACO).

The model also offers strong clues about the future of CMS policy. Its emphasis on outcomes over activities suggests that Medicare Part B reimbursement will continue to move away from fee-for-service logic, especially for chronic disease management and care coordination. ACCESS explicitly embeds telehealth, remote monitoring, and digital health tools, pointing toward more permanent digital health reimbursement rather than temporary flexibilities. Equity is built into the design through required stratified reporting and attention to health-related social needs, signaling that future rulemaking will increasingly tie payment to equity performance. Data-sharing and alignment with Certified Electronic Health Record Technology reinforce that interoperability and FHIR-based exchange remain central to CMS’s regulatory direction.

ACCESS does not stand alone. It is built on the interoperability and prior authorization (PA) foundation created by federal rules. Standardized e-prescribing, real-time benefit checks, interoperable PA, and expanded payer and provider APIs provide the mechanisms needed using health data to measure performance, access, utilization, and outcomes. This alignment also enables real-world evidence generation at scale, allowing digital health tools to be evaluated using routine clinical and claims data rather than bespoke studies.

Implementation will not be simple. Variation across state Medicaid programs introduces challenges related to monitoring access metrics, enforcing transparency, and maintaining consistent oversight with limited resources. Participating organizations also face real compliance and operational risks. Because reimbursement is tied to outcomes, failure to meet performance benchmarks can result in reduced payments or repayment obligations. Participants must also meet strict interoperability, equity reporting, and privacy requirements. Weak security controls or inaccurate stratified reporting could trigger enforcement actions and reputational damage.

ACCESS is already influencing federal work beyond Medicare. It helps establish a common language for outcomes-based reimbursement, shaping initiatives across Health and Human Services, Federal Drug Administration (FDA), and state Medicaid programs. One early example is the Technology-Enabled Meaningful Patient Outcomes (TEMPO) Pilot, which aligns CMS payment pathways with a more flexible, risk-based FDA regulatory approach. This allows selected digital health devices to reach patients sooner while maintaining real-world monitoring and accountability. For patients, it expands access to technology-enabled care. For developers, it creates a clearer path to deployment under CMS reimbursement while navigating oversight requirements. Participating manufacturers may request that the FDA exercise enforcement discretion for: Premarket authorization, Investigational device requirements, while they collect real‑world performance data.

ACCESS is best understood as a proving ground for the next phase of federal health policy. It brings together outcomes-based payment, digital health integration, interoperability, patient engagement, and equity into a single operational framework. If the model succeeds, it could demonstrate that Medicare can meaningfully move beyond fee-for-service without relying solely on Medicare Advantage or large ACOs. More importantly, it may finally provide the sustained focus needed for the most challenging chronic conditions, where both human and financial costs remain highest.

As volunteer models like CMS ACCESS and FDA’s TEMPO pilots reshape how chronic care is financed, measured, and delivered, organizations will need clear insight from Federal Agencies to navigate what’s required and where the real opportunities lie. POCP’s Regulatory Resource Center tracks these developments in real time, translating complex federal and state policy into practical, actionable intelligence. Whether you are exploring participation, assessing compliance risk, or evaluating how these shifts affect your broader strategy, our team is here to help. Contact us to start the conversation.